Continuous Integration

One of the most pivotal challenges in the realm of software development is effectively integrating changes 1. In a small-scale project steered by a single developer, this challenge might appear to be trivial. However, as the magnitude of the project escalates and more individuals join the development fold, the significance of seamless integration becomes paramount.

Historically, integration was often an afterthought, relegated to the tail end of the software development process 2. Postponing it to such a late stage not only amplifies the risk of complex, undetected errors but also heightens the tension as delivery dates loom.

However, the paradigm shifted around the turn of the millennium. Continuous Integration (CI) was formally introduced in 2000 by Kent Beck as an intrinsic part of the ‘Extreme Programming’ methodology 3. CI emphasizes the frequent and early-stage integration of code. By continuously amalgamating new code into the system, developers can gauge its impact promptly. This approach streamlines error detection, enabling developers to tackle issues as they emerge 2. The ability to tie an error to a specific code change reduces error complexity and promotes efficient troubleshooting. Today, CI has become an indispensable practice in software development projects 4.

Martin Fowler, a luminary in the field, eloquently defined CI as:

Continuous Integration is a software development practice where team members integrate their work frequently, typically multiple times a day. Each integration is verified by an automated build system that runs test suites to swiftly detect any integration anomalies. Teams adopting this methodology often witness a significant reduction in integration hiccups, empowering them to produce cohesive software at an accelerated pace2.

Building upon Fowler’s definition, Duvall 5 underscored several vital facets:

- Developers must maintain a conducive local environment for code construction and testing, ensuring their updates do not disrupt the established integration.

- Team members should commit their code to the Version Control System (VCS) daily.

- The integration process must be undertaken on a distinct machine, aptly termed the CI server.

- Only builds that pass all tests can be deemed deliverable.

- Error resolution is of paramount importance.

- A central repository displaying build and test results—often a website—is essential. Most CI tools readily offer such platforms.

Furthermore, Patrick Cauldwell 6 advocates for frequent and early integration. The rationale? The more regular the integration, the less overhead for the team down the line. He distilled the primary goals of CI into:

- Ensuring a consistently available, tested version of the product with the latest modifications.

- Keeping the team abreast of any integration issues as early as possible.

The impetus behind CI is to maintain an error-free, tested product throughout the development life cycle. This avoids the pitfalls of a last-minute integration phase, which is often fraught with errors and consumes both time and resources. More crucially, if project components aren’t integrated during their development, there’s no guarantee they’ll gel cohesively in the final product 7.

Technical implementation of CI revolves around two core components: process automation and a system to showcase results, thereby fuelling the developmental feedback loop 7.

In summing up the tenets of CI, Martin Fowler 1 emphasizes:

- Retaining code in a singular repository.

- Streamlining software construction through automation.

- Implementing automated testing processes.

- Ensuring new code additions undergo integration and construction on the CI system’s machine.

- Keeping the build process agile and swift.

- Providing easy access to the product’s latest executable version.

- Ensuring product status transparency for all stakeholders.

Elements of a CI system

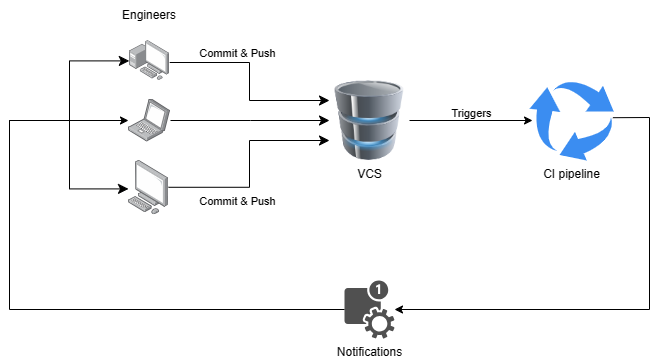

A basic Continuous Integration (CI) pipeline initiates when a new code change is pushed to the repository. The CI server, linked to the repository, gets notified of every new change, subsequently downloading the latest version to initiate the integration process, which will be elaborated on in the subsequent section. Once completed, it communicates the system’s status to the team members.

In computer science, a “pipeline” refers to a sequence of processes or tasks linked such that the output of one becomes the input for the next.

Figure 1: Basic elements of CI (Duvall5)

The system’s primary component consists of the developers. After making code modifications, they run tests locally and compile the code to ensure that they haven’t introduced new errors.

An essential part of every CI system is the Version Control System (VCS). It oversees the changes made to the code and other significant elements. This system establishes a unified access point for all source code, enabling the CI system to fetch the most recent version for integration. Most software development projects utilize a VCS even if they don’t implement CI processes.

The CI Server is responsible for initiating a new build (comprising both compilation and tests) every time a change is added to the repository. They offer configurations to simplify the creation of integration pipelines. Additionally, most come with a web interface to display the build status and previous results. Currently, numerous powerful options are available, both free and paid. It’s worth noting that the CI server should operate on a dedicated machine and not on team members’ computers.

The CI server must automatically conduct software tests, source code analysis, and compile to produce the deliverable product. Therefore, build and test execution scripts are vital. These scripts outline the necessary steps to be executed. Popular tools for this purpose include Make, Ant, Maven, Gradle, among others.

Every CI system should have a notification mechanism to relay results to the team. This mechanism ensures that in the event of an error, the team becomes aware as soon as possible, enabling them to address the issue. While most CI tools offer a web interface to view results, they also support other notification methods like emails, messaging applications, etc.

The integration process

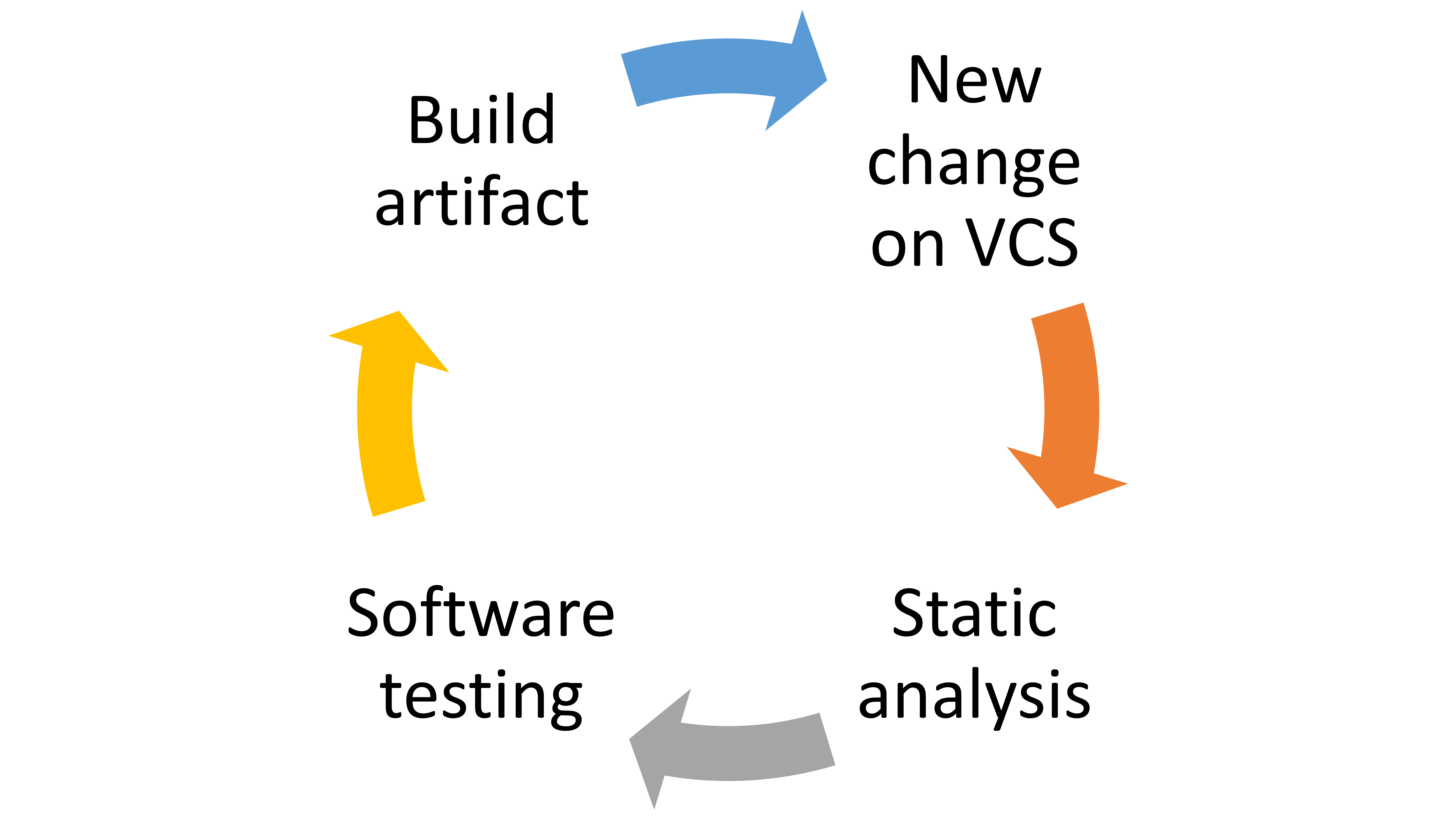

The figure below broadly illustrates the stages of the integration process taking place within the Continuous Integration (CI) system.

Figure 2: CI process flowchart

Initially, the system must retrieve the latest source code version each time a new change is pushed to the Version Control System (VCS). Two mechanisms facilitate this. The first involves setting up the CI server to periodically check the VCS for updates. The alternative is to establish a commit hook within the VCS, ensuring that the CI server receives notifications whenever changes are made.

After obtaining the code, the CI server can be configured to scrutinize the source code for potential undetected errors, be they syntactic, logical, or patterns that might lead to faults. Various tools aid this process. For instance, Java boasts utilities like FindBugs, CheckStyle, and PMD, while Python has Pylint. JavaScript can be analysed with tools like JSLint or JSHint. An example of a code analysis criterion could be ensuring every developed method has a cyclomatic complexity8 under 10. By employing automated source code inspection, one can assess code correctness, spot duplicate portions, and expedite the time between error detection and rectification. While automated inspection might not catch every error, the results can approximate those of peer reviews, thereby lightening the team’s review load.

The subsequent step revolves around automated test execution on the product. This automation is paramount to successfully implementing a CI system. Thus, developers can confidently make alterations, knowing a robust testing framework safeguards against compromising existing functionalities. Some popular tools in this domain include Junit, JBehave, and Selenium, which not only facilitate test drafting but also generate comprehensive reports, often as visualizations or web pages. Several software testing levels exist, such as unit tests, integration tests, and system tests. In the CI pipeline context, the focus rests on automating unit and integration tests, with system tests’ automation being recommended but not mandatory.

Once the tests pass, the CI pipeline advances to compiling the source code. During this phase, the source code morphs into one or multiple files or packages, ready for distribution and user execution. This process’s specifics hinge on the employed programming language. For instance, languages like Java necessitate code compilation, resulting in an executable. Conversely, languages like Python might involve stricter code structure checks without generating any binary files.

Throughout this integration journey, the team should steadfastly adhere to three fundamental rules:

- Locally run tests and compile software before integrating it into the VCS to minimize error introduction chances (avoiding “breaking the build”).

- Avoid pushing new code to the VCS if the CI server flags errors (indicative of a “broken build”).

- Should the CI server report faults, code modifications should exclusively aim at rectifying them.

Core principles and practices

Martin Fowler2 identifies a set of foundational elements intrinsic to every Continuous Integration (CI) system. While some of these have been touched upon earlier in this chapter, we will succinctly encapsulate them here for clarity:

- Centralized Code Repository: Retain all code within a singular, unified repository.

- Streamlined Compilation and Build Process: Entirely automate the compilation and construction workflows, negating manual intervention.

- Full-Spectrum Automated Testing: Ensure all software tests are automated, driving efficiency and precision.

- Daily Commitment: Encourage the team to consistently merge their changes to the repository on a daily basis.

- Stringent Integration Checks: Each alteration made to the Version Control System (VCS) undergoes rigorous integration processes within the CI system.

- Prompt Error Rectification: Should the CI system flag any issues (indicative of a “broken build”), immediate action is imperative. Either rectify the flaw or reverse the change to ensure the repository’s latest version remains operational.

- Swift CI Procedures: Aim to complete the CI process rapidly—ideally within 15 minutes or less. This approach ensures timely integration and facilitates the expedited delivery of results.

- Universal Access to Latest Executables: Always provide the team with access to the most recent executable or deliverable package, promoting transparency.

- Real-time Product Status Visibility: Grant every team member the ability to monitor the product’s status at any given moment, fostering informed decision-making.

Benefits

The overarching consensus within the software community is that the implementation of a Continuous Integration (CI) process yields an array of substantial advantages. Duvall5 outlines these core benefits in his publication.

Risk Mitigation: Adopting frequent integration minimizes project risks. It facilitates early detection of issues and offers a continuous snapshot of the product’s health. By identifying these issues early in the development cycle, there’s a consequent reduction in both the cost of fixes and the risk of releasing a subpar product. Furthermore, automated inspections provide real-time insights into the product’s size, code complexity, and other metrics. This automation diminishes the chance of human-induced errors.

Minimization of Manual Repetitive Tasks: Automation curtails the need for recurring manual tasks such as compilation, inspection, test execution, and report generation. This efficiency not only leads to significant time and cost savings but also allows teams to focus on activities that directly enhance product value. It liberates team members to dedicate more time to addressing new requirements or rectifying existing product issues.

On-Demand Availability of a Functional Product: A hallmark of CI is its ability to deliver a functional software product at any given moment. This is invaluable for stakeholders, offering them a rapid glance into product development progress. By leveraging CI, errors can be swiftly detected and remedied soon after a new change is introduced. This is far more efficient than uncovering them close to the release date when they are more expensive and challenging to amend. Such issues, if left unchecked, can lead to delivery delays, unsatisfied clients, escalated costs, and more. This ties back to the concept of the “Broken Window Theory”9, which, in essence, postulates that a product marred by numerous issues or perceived disorder can demotivate teams from addressing them.

Enhanced Project Transparency: Implementing CI augments visibility into the project, rendering the development process more transparent. It aids project management with up-to-the-minute information, making it straightforward to gauge product quality, error trends, and more.

Elevated Product Confidence: The CI environment bolsters confidence in the product. Team members gain immediate insights into the ramifications of their changes, enabling them to promptly rectify any emergent issues.

Challenges

While Duvall5 has extolled the virtues of Continuous Integration (CI) in his works, he also highlights potential challenges that might deter development teams from embracing it fully or realizing its benefits.

Bias: A widespread misconception is that CI system implementation is exorbitant and would escalate development costs due to its prolonged setup and maintenance. Contrarily, most software development projects already involve phases like inspection, testing, compilation, and integration, even if they don’t explicitly use a CI system. A common refrain is that there’s insufficient time or funds for CI system implementation, but the reality is that far more resources are spent performing redundant manual tasks throughout the development cycle. Furthermore, an automated CI system is infinitely more manageable and consistent compared to disparate manual processes.

Disruption Fears: Projects in advanced development stages often fret that integrating a CI system would overhaul their established workflows, spawning significant delays. It’s pivotal to recognize that CI system implementation can be incremental. Teams can address one integration stage at a time, gradually ramping up the integration frequency as confidence builds.

Overwhelming Failed Integrations: When CI practices aren’t diligently applied, there’s a risk of encountering an excessive number of failed integrations or “broken builds.” This could stem from developers bypassing local tests before uploading their changes to the Version Control System (VCS). A surge in failed integrations can erode trust in the CI system, reminiscent of the “Broken Window Theory”9.

Perceived Additional Costs: There’s an apprehension among organizations about incurring extra expenses either for procuring CI product licenses or securing hardware to support these systems. However, this expenditure pales in comparison to the latent costs of late-stage integrations, where issues are discovered near the release date, far removed from their inception. On a brighter note, the current landscape is rife with a myriad of free and open-source alternatives, obviating any additional costs.

References

Continuous integration. ThoughtWorks, 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Fowler, Martin. Continuous Integration. 2006. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Beck, Kent. Embrace Change with Extreme Programming. IEEE Computer Magazine, (c), 70-77. 1999. ↩︎

Rodriguez Pilar, Markkula, Jouni, Oivo, Markku, & Turula, Kimmo. Survey on agile and lean usage in Finnish software industry. In Proceedings of the ACM-IEEE international symposium on Empirical software engineering and measurement - ESEM ‘12 (p. 139). ACM Press. DOI: 10.1145/2372251.2372275. 2012. ↩︎

Duvall, Paul M., Matyas, Steve, & Glover, Andrew. Continuous integration: improving software quality and reducing risk. Pearson Education, Inc., 2007. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Cauldwell, Patrick. Code Leader: Using people, tools and processes to build successful software. Wiley Publishing, Inc., 2008. ↩︎

Humble, Jez & Farley, David. Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases through Build, Test and Deployment Automation. Addison-Wesley, 2011. ↩︎ ↩︎